Mount Yengo (Yunge) on the 29th January 2009 (Representation)

Day Shift – 17/02/2009 – 02:10 PM

Presenter: Carol Duncan

Producer: Jeanette McMahon

Interviewee: Gionni Di Gravio, Archivist, Newcastle University

University of Newcastle Archivist Gionni Di Gravio discusses his recent field trip to the Wollombi District to view and examine Aboriginal Rock art in the area. At a Wollombi Gathering held on the weekend to a packed audience at Laguna House he and a number of speakers from the University of Newcastle and the University of Sydney presented their work on the Antiqities of the Wollombi District and its great importance to the region. It is our Uluru and needs to be properly researched, documented and managed to safeguard it from natural erosion and vandalism. To illustrate his presentation he used exerpts from the work of Lieutenant Breton, who travelled through the area in the 1830s. For today’s broadcast he has brought in an original edition of Breton’s work and Issac Nathan 1848 work containing an Aboriginal song documented by Eliza Dunlop in the Wollombi District in the 1840s.

Broadcast Notes:

On Thursday 29 January 2009 Amir Rezapour Mogadam (Conservator) and myself were asked to accompany representatives of the Binghai Aboriginal Sites Team to examine Rock art sites in the Yengo Sandstone Country (Wollombi district).

This region is arguably home to the richest source of rock art in the world, and Yengo is as important and significant a site as Uluru is to Central Australia.

Unfortunately the area is subject to a number of ongoing threats (natural and man-made) and we were asked to advise on conservation issues relating to the extensive rock art of the region with a view to forging closer ties with the University’s research and teaching capabilities.

A member of the team also addressed the first meeting of Coal River Working Party on 2 February 2009.

Mr Garry Jones briefed the CRWP on Yengo National Park’s history and highlighted the need for better management and conservation of the area. There is a need to record and protect this area which is rich in Aboriginal Rock Art. Mr Jones asked that the CRWP support the fostering of closer links between the University of Newcastle and organisations with an involvement or interest in the park, including the Wollombi Valley Arts Council, land owners and Aboriginal groups. The University of Newcastle could provide a scholarship for a post graduate course in Aboriginal Art Identification and Recording. It was resolved that the CRWP would investigate fostering closer ties between the University and the Binghai (Brother) Aboriginal Sites Team for the future teaching and research possibilities of the Yengo National Park.

A ‘Library of Alexandria’ in stone.

I was invited to speak at a Wollombi community gathering on the 14th February 2009. The MC of the evening, Mr Claude Aliotti, described the extensive Aboriginal cave and rock art of the region as a ‘library’. He is certainly correct. It is a library in stone, full of stone books, just like a petrified library of Alexandria, right here on our door step. (It could be called our Paleo-Biblioteca Wollombiana) Whereas, the original Library of Alexandria was completely destroyed by a series of despotic raids, ours still remains, but unfortunately not free from attack.

What follows is a precis of my presentation to the local community.

THE ANTIQUITIES OF THE WOLLOMBI DISTRICT

My personal account of this magical landscape

I work in the Archives of the University of Newcastle where we hold important research documents relating to the Newcastle and the Hunter Region. I rarely get out of the ‘dungeon’ and so it’s a real treat when I’m invited to visit some of these important areas that I have seen represented in the documentary accounts in books, articles and manuscripts.

One such opportunity arose the 29 January 2009 when our conservator Amir Rezapour Mogadam and I were asked to accompany Garry Jones and representatives of the Binghai Aboriginal Sites Team to examine Rock art sites in the Yengo Sandstone Country (Wollombi district). Amir had done his Masters on lichens and the Team were very interested in advice on what could be done about lichens on the sandstone engravings.

There is no way to capture the beauty of the place.

We arrived at dusk and made our way to the Northern Map Site or Flat Rock at the Finchley Park Reserve.

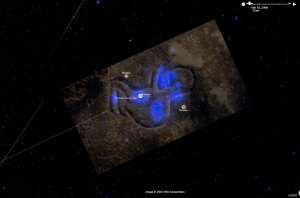

Mount Yengo (Yunge) on the 29th January 2009 (Representation)

There is no way I could capture (with my limited camera skills) how beautiful the sight of the crescent moon over Mount Yango with Venus to its upper right was to behold. I’ve managed to construct one as best as I can from an Astronomy program that can reproduce the heavens from any point on the planet. There was a fortunate gap in the trees to allow Venus to shine through, as the sun was descending into the west. Yengo was in an errie glow, and the scene gave you the impression it was just for you to see.

We walked a short distance to what is known as the Northern map site and began photographing the engravings.

At night, under lamp light the engravings really came alive, and features that were invisible during the day, became easy to see. At night, with the blazing starry heavens overhead, the Sky Hero’s angular mouth became fascinating.

I became fascinated by the Orion constellation above us, and began to see similarities between this figure and the stars of that constellation above. But after a number of futile attempts to put it together as I saw it that night, one needs to remember that we have to turn our constellations upside down, and join the dots in a different way to fully appreciate the figure as it impressed the Aboriginal artisans that crafted the original engraving. Look especially at the mouth (formed by what looks to be the stars below Rigel, and also those of Orion’s belt (Mintaka, Alnilam and Alnitak), his elongated form clutching a boomerang, his legs represented by the stars Bellatrix and Betelgeuse and his privates made up of the pointed constellation of stars ending in Meissa between them.

Another that fascinated me was a small engraving of a turtle/foetus creature kneeling towards Yango. Again I kept looking at the magnificent starry sky and thinking of the Pleiades.

It would be interesting to map out this site with the heavens above and see whether there is a correlation. As the stars were in equal competition the engravings for our attention I could not believe that they could not have been created without the sky as some inspiration.

Unfortunately there was also later engravings there from ‘Trace’ and what looked like a bull dozer. What will these ‘engravings’ tell future generations of our culture and beliefs?

The next day, the starry heavens disappeared and the I woke up to a sky full of clouds. Mount Yengo had disappeared, I couldn’t find it, and I was convinced that this place was a really magical place. It is on a parr with anything anywhere in the world. It is our own Etruscan tomb landscape on our doorstep and much much more.

It was a magnificent experience, but the desperation of our hosts at the damage that was occurring out there through ignorance and malicious vandalism was profound.

We are all horrified by what the Taliban did to the stone Buddhas in Afganistan, but we have our own versions running around the countryside here in our equivalent Uluru and its time that something happens because we owe it to those ancient artisans to look after the place as we have become its custodians now.

Back on the 10 June 2008 two rising sun colar badges were discovered in one of the mass burial pits being excavated in Fromelles. In these pits lay the remains of Australian and British troops. In an inspiring and heartfelt gesture the owner of the land, Madame Marie Paule Demassiet, donated this land (sacred to another people) to be a permanent memorial. We need to find a similar spirit here for this country. It is a living library and an archive in stone. It is a stone book.

The Historical Accounts

Wollombi is the place where the waters meet and forms a geographical dividing line between a number of Aboriginal tribes Awabakal, Wanarua, Darkinung and Kamilaroi. The early accounts don’t name the tribes, Breton mentions those of the ‘Wollombi’, ‘Illarong’ and ‘Comleroy’ (or Kamilaroi – with whom they had battles).

The Tribe who lived at Wollombi was probably the Darkinung, but there is also evidence that Awabakal people had close relationship with the area as well. According to Mrs Eliza Dunlop who lived in Wollombi during the 1840s their leader was Boni. (Gunson-Threlkeld p.7)

The beginnings of Wollombi lie in Governor Macquarie’s 1818 decision to commence a settlement at Wallis Plains (Maitland). He chose John Howe, Chief Constable at Windsor to lead expedition to find an overland route, reaching the Hunter River just above Jerrys Plains in 1819. John Howe’s second journey in 1820 reached the Hunter River via Bulga and Cockfighter’s Creek (lower part of Wollombi Brook – named after one of the horses in the expedition) and discovered Patrick’s Plains (Singleton). In 1823 Howe’s Valley Road was begun and began to move settlers into the region. In 1825 Surveyor Heneage Finch found overland route from Wiseman’s Ferry through Wollombi to Wallis Plains. During the 1820s and 1830s work proceeded on the Great North Road, by 1831 the stretch through Wollombi was opened.

During this period around in the early 1830s Lieutenant William Henry Breton R.N. traveled through the region. He published his account in Excursions in New South Wales, Western Australia, and Van Dieman’s Land during … 1830,1,2,3. (1833)

Breton’s overall opinion?

“Speaking collectively be confessed I entertain very little more respect for the aborigines of New Holland than for the ourang outang in fact I can discover no great difference.” (Breton 196).

This appears harsh until we read earlier:

“Their manners are scarcely formed yet if I may judge from the behaviour of one of them he was trying to teach me the mode of throwing the spear but observing me to be somewhat clumsy he took it out of my hand remarking at the same time Oh you d– d stupid This was not polite in the barbarian but so long as the natives learn their English from the convicts I fear we shall get no better language from them I am not at all convinced that this black intended to make use of an improper expression” (Breton, 91)

Breton mentioned that around 60 natives accompanied them on their travels while they were passing through Wollombi.

“These people consisted of two tribes one from Illarong the other belonging to the Wallombi and were on their way to wage war with another tribe.” (Breton, 91)

“We found the Wollombi natives very friendly towards us but they seemed to have taken a much greater liking to some swine belonging to the gentlemen with whom I was staying; of these they slew several and were bearing them off in triumph, when to their extreme dissatisfaction, not to say dismay, the superintendant made all possible haste in pursuit with his establishment of dogs. One of these sable stealers of pork was driven into a tree, and another was fairly run down and brought to bay, crying out all the time in a most unbecoming manner; an evident proof that he did not belong to the sect of the stoics. The superintendant took great care that the dogs did them no injury, his object being only to frighten the depredators; and having recaptured his pigs..” (Breton, 198)

He then cites another example of tribe that left a shepherd to die on an ant hill:

“A neighbouring tribe killed, in 1830, more than 100 sheep belonging to a settler who has a farm near Wallombi; they then bound the shepherd hand and foot, left him upon an ant’s nest ( a bed that Guatimozin himself would not have envied him) and then departed. The man was rescued before he had sustained any injury, and most fortunately for him for these ants sting and bite in a way that would astonish any one, as I know from experience, having twice suffered from their attacks, to my great annoyance, for many days afterwards. The large black ant can cause a pain almost as acute as that of a wasp! A party of soldiers, or dismounted police, were sent after the offenders of whom they killed several.” (Breton, 199)

While noting some sympathy his honesty is brutal:

‘But on the other hand, they should not be permitted to harrass the settlers with impunity: we have taken possession of their country, and are determined to keep it; if, therefore they destroy the settlers or their property they must expect that the law of retaliation will be put in force, and that reprisals will be committed upon themselves. This has rarely been the case, as they have been wantonly butchered and some of the Christian (?) whites consider it a pastime to go out and shoot them. I questioned a person from Port Stephens concerning the disputes with the aborigines of that part of the colony, and asked him if he, or any of his companions, had ever come into collision with them as I had heard there prevailed much enmity between the latter and the people belonging to the establishment? His answer was “Oh we used to shoot them like fun!”’ (Breton 200-201).

Elsewhere he recorded a mystifying description of a Kamilaroi burial ceremony

“In an affray that took place on the Wollombi between two tribes, four men and two women of the Comleroy tribe were slain; they were buried at a very pretty spot in the following manner. The bodies of the men were placed on their backs in the form of a cross, head to head, each bound to a pole by bandages round the neck, middle, knees, and ancles, the pole being behind the body; the two women had their knees bent up and tied to the neck, while their hands were bound to their knees; they were then placed so as to have their faces downwards: in fact they were literally packed up in two heaps of earth, each of the form of a cone, about three feet high and rather removed from the cross; for their idea of the inferiority of the women will not allow them to be interred with the men. The neatness and precision observed with respect to the cross and cones is very remarkable, both being raised to the same height and so smoothly raked down, that it would puzzle the nicest observer to discover the slighest inequality in the form. The trees for some distance around, to the height of fifteen or twenty feet, are carved over with grotesque figures meant to represent kangaroos, emus, opossums, snakes, &c. with rude representations also of the different weapons they use. Round the cross they made a circle, about thirty feet in diameter, from which all rubbish was carefully removed, and another was made outside the first so as to leave a narrow interval between them: within this interval there was laid pieces of bark, each piece touching the rest, in the same way that tiles do. The devil, they say, will not leap over the bark, and cannot walk under it!

Such evident pains and labour to make a place of sepulture, struck me as being not a little extraordinary in a people so very indifferent about most other matters; but I could discover no satisfactory reason why such care had been taken of these members of their tribe. They said it was the way in which they usually buried their dead, but this practice is by no means common. Four Waddies (clubs) were stuck into the earth in the centre of the cross; and these they informed me were left in order that the deceased might have some arms, “when they jump again,” so as to be enabled to drive away the devil, and prevent him from taking them again into the earth! (Breton 203-205)

This illustration of a native burial from Oxley’s Journal could give you an idea of what these things looked like:

Illustration from: Journals of two expeditions into the interior of New South Wales, undertaken by order of the British government in the years 1817-18 by John Oxley (London : John Murray, 1820)

When I enquired about this, I was told that they would bury their dead in a termite nest, taking the top off, placing the dead within, and putting the top back on, and they would smooth it over, the insects would seal it up again. This is also interesting to investigate further, as to whether any of these burial mounds still exist.

The Aboriginal World of the Wollombi District

Most of the notes below come from a magnificent book by Bill Needham back in 1981 entitled [Cover title] Burragurra: Where the Spirit Walked. Aboriginal Relics of the Cessnock-Wollombi Region in the Hunter Valley of NSW. [Title page] A Study of the Aboriginal Sites in the Cessnock – Wollombi Region of the Hunter Valley, NSW by W.J. Needham. 1981. Mr Needham wrote his book out of a concern for the protection of the area, and a need to raise awareness of the magnificent rock and cave art in the Region.

Wollombi Valley was defined by the following tribes – Darkinung Tribe (Valley itself extending south to Hawkesbury and east to Peat’s Ridge), to the east Awabakal Tribe (Lake Macquarie), Wonarua (where Wollombi Brook met the Hunter River near Singleton the southern boundary), to the west the Kamilaroi.

Tribes were made up of clans or family group e.g. Wollombi clan.

Aboriginal place names in the region include e.g. Wollombi (place where waters meet); Yengo (the stepping up place); Watagan (Place of many ridges) Laguna (Near a mountain stream); Congewai (Valley of the Lily); Tomalpin (A small hill); Bulga (Isolated mountain).

Mr Needham also recorded a number of myths and legends of the Wollombi including:

The Legend of the Crimson Waratah (from S. Brown to W.J. Needham) – Aboriginal legend holds that the Waratah did not always flower into crimson crown but originally it bloomed in white flowers. One day a wongah pigeon was flying across the gully and was attacked by a hawk, its blood spilled onto the flowers, and from that day on it flowered into crimson.

Legend of the Giant Lizard at Yellow Rock (Broke) (from Eric Taggart to W.J. Needham) I have also had this story related to me from Brian Laut who received it from Eric Taggart who in turn received it from Tommy Dillon. A great lizard (or goanna) wended its way across the land from the coast creating valleys and mountains. As it made its way towards the plains country it was met by the warriors there who commanded it to stop, it resisted, and the warriors killed it and smashed its head. It can be seen to this day petrified as Yellow Rock at Broke. To ensure that it stays that way, to the left of the road at Broke lies a line of rock formations which are said to be the Kamilaroi warriors who stand guard, just in case it chooses to revive itself and continue its journey.

Mount Yengo. Place where the Aboriginal spirit hero, the All Father (Baiame), stepped back into the sky world after his journeys on the earth. While on earth he made man from one of his legs, and is therefore depicted in some rock art as having one leg. His travels are also documented at various sites.

The Flood. The Lake Macquarie tribe (Awabakal) believe in a great flood that covered all the mountains. Proof can be found in the existence of fossilised sea shells on the tops of the mountains. (see Threlkeld’s Reminiscences – ed. Gunson, 64)

Mrs Eliza Hamilton Dunlop, wife of the local police superintendant in the 1840s also recorded some of the Spirit Beings of the Wollombi natives. They included:

Buggee – old fellow, very ill, short, fat and balding. All sickness is attributed to him.

Yaree Yarwoo – a four-eyed spirit, who carries a large bag and gets into it when he is cold. All sickness is attributed to him.

Milegun – This spirit has no hair, but immense nails for digging into the bodies of the blacks.

Muree – This spirit resides in trees and emits fire. [Bill Needham suggests that this is a reference to bush fires when eucalyptus trees at some distance from the fires erupt in flames due to the volatile oil].

Wabbooee – This as the greatest spirit of them all. He commands the seasons and the weather. He resides in the North. Water of a blood colour springs up all around him. He presides over the day. It was irreverent to speak about him, a crime punishable by death. It was believed that when he died rocks would fall from the sky destroying the world.

Wallatu – God of Poesy. He comes in dreams and transports the individual to a favoured site, where he was inspired with the gift of poetry. These songs were few in words but varied in musical tone.

The Rev. Lancelot Threlkeld was very impressed with Eliza Dunlop rendering of an Aboriginal song. (see Threlkeld’s Reminiscences ed Gunson, 58)

Eliza Dunlop (Mulla Villa c1840s) writes of ‘Wallatu’:

A lady, Mrs E.H. Dunlop, published some years ago in one of the Sydney papers, a specimen of “Native Poetry,” and states thus:

There is a god of Poesy, Wallati, who composes music, and who, without temple, shrine, or statue, is as universally acknowledged as if his oracles were breathed by Belus or Osiris: he comes in dreams, and transports the favoured individual wrapped in visioned slumber to some bright warm hill, where he is inspired with the rare and supernatural gift.” ( with corrected text of note 75) This very individual, Wúllati, or as white folks used to call him, Wollaje, always confounding the sound of t with a j, lived near our establishment, he was esteemed highly by the tribes, and in an increasing ratio as they were nigh or more distant from this individual. No doubt he formed the delightful subject of their evening Soirees, and also of their midnight dreams. He favoured me several times with his company, and perhaps thought it an honor when he made proposals to me for a matrimonial alliance with one of the members of my family, much to the amusement of us all. He was very old, thin, small headed, bald man, of a most cheerful disposition, with a smile always on his countenance except in the presence of strangers; and whenever he came to our tribe, his company was much enjoyed, an evening feast was provided, and the chicest tit-bits were set before the toothless guest. Oft were his gibes wont to set their table, on the green grass, in a roar of laughter, and their festive board, generally the bark of a tree, was enlivened before it ended in the midnight hour with his song and dance, assisted with his own voice and musical accompaniment of two sticks, beating time to the divine inspiration of the sacred muse. (see note 76: ) The following song, composed by Wúllati, translated and published, some years ago by Mrs E.H. Dunlop, is an excellent specimen of the Poetry of the Aborigines, and ought not to be lost though the Poet and his tribe is now no more.

“NATIVE POETRY”

“Nung – Ngnun

Nge a rumba wonung bulkirra umbilinto bulwarra!

Pital burra kultan wirripang buntoa

Nung-Hgnun

Nge a rumba turrama berrambo, burra kilkoa;

Kurri wi, raratoa yella walliko,

Yulo Moane, woinyo, birung poro bulliko,

Nung-Ngnun

Nge a rumba kan wullung, Makoro, kokein,

Mip-pa-rai, kekul, wimbi murr ring kirrika;

Nge a rumba mura ké-en kulbun kulbun murrung.”

Thus “Translated and Versified by Mrs E.H. Dunlop”, of Mulla Villa, New South Wales. (In a newspaper.) [Mulla Villa (house by the river erected at Wollombi in 1841)

“Our home is the gibber-gunyah,

Where hill joins hill on high;

Where the turruma and berrambo,

Like sleeping serpents lie; –

And the rushing of wings, as the wangas pass,

Sweeps the wallaby’s print from the glistening grass.Ours are the makoro gliding,

Deep in the shady pool;

For our spear is sure, and the prey secure…

Kanin, or the bright gherool.

Our lubras sleep by the bato clear,

That the Amygest’s track hath never been near.Ours is the koolema flowing

With precious kirrika stored;

For fleet the foot, and keen the eye,

That seeks the nukkung’s hoard; –

And the glances are bright, and the footsteps are free,

When we dance in the shade of the karakon tree.

Gibber-gunya – Cave in the rock.

Turruna [sic] and Berrambo – War arms.

Wanga – A species of pigeon.

Makoro – Fish.

Amygest – White-fellow.

Kanim – Eel.

Gheerool – Mullet.

Bato – Water.

Kirrika – Honey.

Nukkung – Wild bee.

Kurrakun – The oak tree”.Such is a fair specimen of Song, translated, with a little political licence. The orthography, although different from the system laid down in my Australian Grammar, sufficiently conveys the sound to enable me at once to discover the dialect of Wúllati the Poet who resided, near our residence on the sea shore, close to moon Island, until he died. The word “Nung ngnún” (See note 77 – ) means a song, and when attached to the verbalizing affix wit-til-li-ko becomes Nung-ngún-wit-til-li-ko, according to the idiom of the language, For to song a song, – English, to sing a song.

Threlkeld was therefore able to show from Mrs Dunlop’s accurate rendering of the song that it was sung in a dialect that originated in Lake Macquarie, therefore showing that the human personification of Wullatu was a Lake Macquarie (or so called Awabakal) man.

Compare this account with that published prior to this in Issac Nathan’s The Southern Euphrosyne (1848).

There is so much more to learn and to discover in this district. I hope that we ta the University of Newcastle can help in setting up something like a research outpost out there so that the rock art can be preserved, safeguarded, documented, researched, and protected for future generations to come. We hope to also help in expanding it’s natural World Heritage listing to include its rock art as well. It is one of our region’s most sacred places, and deserves better. All roads lead to Yengo.

Yours sincerely,

Gionni Di Gravio

February 2009

Pingback: Cultural Collections Annual Report 2009 « UoN Cultural Collections

i am really interested in my culture and would love to know about more sites… would u know of any not well known sites?? i heard of one at wollimbi its supposably on someones property but they let public access through to the site.. i have tried to find it but did not succeed… its supposed to be right at wollimbi pub then up the road a short distance. any help would be much appreciated.. thank you..

cara lloyd

Thanks that was a brilliant description of the place. It’s a beautiful part to be.